There was a time on Tiktok that I could not escape Atomic Habits, the best-selling habit manual promising, “an easy and proven way to build good habits and break bad ones.” I saw a fair amount of people praising the book, often in oddly-hushed tones, starting their videos with, “Have you read Atomic Habits? It has CHANGED MY LIFE.”

Recently, I saw that the author of Atomic Habits, James Clear, was on Design Matters, the podcast hosted by Debbie Millman. Debbie Millman is a fastidious researcher and a skilled interviewer. I started the podcast expecting some kind of enlightenment, and finished feeling rather flat. I wasn’t particularly intrigued by their conversation, nor by James Clear himself.

Big Brother Algorithm caught wind of this, (or perhaps it was really coincidental) and that same day I saw a Tiktok video from Paige(@sheisapaigeturner), a mom of four, who’s videos focus on parental load and equal partnership. She said she would never take advice from a self help book written by a man, particularly a childless man, saying that their reality is too different than hers. Someone in the comments mentioned that Atomic Habits was a perfect example of male advice that doesn’t suit women, and I thought, “Hmmmmmmmm, could this be why that podcast fell so flat for me?”

So, I hatched a plan.

I decided to read both Atomic Habits and The Creative Habit by Twyla Tharp and put both methodologies to the test. Since the beginning of this newsletter, I’ve intended to plan my outfits every week. I’ve never succeeded. I think outfit planning would simplify my mornings, while also helping me look and feel closer to myself. Can either of these books get me into the habit of planning my outfits? Will the female point of view speak more to my reality than the male point of view?

This week, I read Atomic Habits and it has inspired all five outfit prompts. (Outfit inspiration is everywhere!)

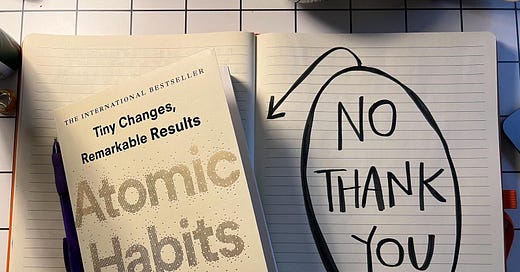

I hated Atomic Habits.

I expected Atomic Habits to be a groundbreaking new methodology, but it’s actually a compilation of other people’s research, neatly organized. James Clear isn’t any kind of academic researcher, but rather a guy who fell into writing about habits because the topic got more readership on his blog.

As a public persona and as a writer, James Clear is not interesting. He writes about habits but seems to have no zest for them. He knows plenty. He’s well researched, but colorless. He talks about his own use of habits solely in the introduction of the book (During his episode of Design Matters, he said this was a decision forced by his publisher) and apparently, he used good habits to become a better collegiate athlete.

James Clear the man isn’t interesting, but his writing is worse. Each chapter follows the same format: someone’s else’s story or research, elaboration on that research as related to habits, a graph. There are no jokes, no oddball chapters, no personal anecdotes. It felt like reading the instruction manual for a blender. Couple that with the fact that the book is significantly too long, and by the time I made it to the final chapters, I would have preferred to smack myself in the face with it instead of continuing to read.

Most irritating to me is the book’s point of view. Most of Clear’s strategies rely on piggy-backing new habits onto current habits. These strategies assume that everyone is operating on a set, unchanging, predictable, daily schedule. At the time of publication, that was likely James Clear’s reality, but that’s not mine, nor is it the reality of most people. There is no deviation from this assumption. There is never mention of how to handle his strategies if a daily schedule is rare, and most of your days are ruled by chaos. There’s no mention of recovering a habit after a change in routine like vacation, or sickness, or if you have a job with erratic hours, or if you’re a caregiver. The strategies provided are tidy and organized, and sound good enough in their basic descriptions, but lack consideration of the many events in real life.

Additionally, and I fully admit that this is a me-problem, so much of the research and information James Clear draws from in this book is about how our brains haven’t evolved in tens of thousands of years, and how to have good habits we just need to trick the caveman-grade brick inside of our heads, and I find that perspective tedious. Also, the majority of his examples of habits are all about fitness which I found boring, and lacking in any kind of creativity or consideration of who might be reading his book.

Suffice to say, I didn’t feel spoken to by James Clear. But tone and allure aren’t everything, and I rather begrudgingly admit that there are some decent ideas in Atomic Habits. Boiled down, the book advocates for making good habits easy to complete, and bad habits very difficult. (That’s it. That’s the whole book.) It offers a variety of tactics to accomplish this.

My failure at planning outfits has been because it’s too hard. On the weekends, the window of time I have to outfit plan is very small. It’s often made smaller by my own tendency to publish this newsletter late and by the unpredictability of life with small children. I’m going to take James Clear’s advice and start simpler. Instead of planning entire outfits, I’m only going to plan the base layers. I think I can handle finishing an outfit each morning while still meeting my goal of getting dressed everyday in outfits that I feel good in.

James Clear emphasises that our environment plays a large role in how easy it is to accomplish a goal. I’m already in the habit of staying on top of our household’s laundry, but usually by the end of the week, if anyone is lacking clean clothes, it’s me. On Fridays, I’m going to make an effort to have my clothes clean and put away, and available for planning.

So, now for the prompts: (As irritated as I was by this book, I’m intrigued by these prompts, and I hope you feel the same!)

In Atomic Habits, a study is cited that found that if people were given nice-smelling, good-lathering, hand soap, they were more likely to keep up the habit of handwashing. The habit wasn’t successful because handwashing is a sanitary practice that wards off all kinds of disease, but rather because the process was instantly gratifying. Can you make the experience of getting dressed more instantly gratifying? Can you reward a good outfit with your best perfume, or a dance party, or chocolate square? (If you’re unsure of what would be instantly gratifying, send me your OOTDs and I will shower you and your outfits with praise!!!)

One tactic suggested for making bad habits more difficult is to make them invisible. This week, if you have clothes that you reach for often, out of convenience, but don’t actually like, can you hide them? Can you stuff them in the bottom of the laundry hamper, or the back of your car, and force yourself to wear “you” clothes?

I continue to be perplexed by James Clear’s cult-like following, solely because he, himself, is not a memorable personality. So many of the runaway bestseller self help books of the last ten years were written by big personalities with dramatic stories and a bombastic writing style. (I’m thinking of Jen Sincero’s You Are a Badass series and Marc Manson’s The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck.) If, like James, you became an unlikely cult leader, who would be following you and what would you be teaching them? How would the cult leader version of you dress? Can you plan an outfit befitting this persona?

Can you make the habit of getting dressed easier this week, and repeat an outfit that you’ve loved? Can you take the friction out of future outfits, too, and start an outfit log, so on uninspired days you have plenty of good looks to choose from? (I have an album on my phone with pictures of outfits that I’ve loved. My friend, Stephanie, known as stephneusews on Tiktok, shared a method of making all of these pictures into a note, and I love this idea more! Then you can see all of the outfits in one place.)

The tactic of saying our actions aloud (or Pointing-and-Calling) is mentioned in the book as a way to draw attention to the habits we do on autopilot, saying that if you don’t see something, you can’t change it. I’m curious about how this same tactic could effect getting dressed. What would the rest of your day feel like if you started it by saying aloud, “I am wearing my favorite jeans! They make my butt look great!” or “This outfit is the perfect representation of me!” Can you try Pointing-and-Calling an outfit this week? How does it change both your experience of the outfit itself, and your mood throughout the day?

The next instalment of this experiment will be two newsletters from now. (I’m optimistic that will both give me time to test the strategies above, and read A Creative Habit.) Have you read either Atomic Habits or A Creative Habit? What are your opinions? Do you plan your outfits every week? I’d love to hear how you approach the habit of getting dressed.

Wishing you a week of cult-like following and adoration,

Rebecca